Podcast Testi

Episode 13 - Rome under Augustus, the greatest city of the ancient world

Written by Marcello Cordovani

Like Caesar, Octavian not only administered but aimed at carrying out a gigantic reform that would renew the whole Roman society on the model designed by his uncle. To do this, he formed around himself a sort of ministerial cabinet: there was a great organizer, Marcus Agrippa, a great financìer, Maècenas, and several generals, among them his stepson, Tiberius. Maècenas was so active in financing and promoting arts and artists that his name has crossed the centuries and become a byword in many languages for a well-connected and wealthy patron who encourages artistic production.

As aristocrats complained of being excluded from this cabinet, he chose about twenty of them, all senators, to form a sort of crown council. The assemblies continued to meet and discuss, but less and less frequently and without ever attempting to reject any proposal from Octavian.

He continued to accumulate enormous powers: he was consul, he held command over many provinces, had immense wealth, and thousands of veterans were bound to him with a bond of personal loyalty.

Over the years, his institutional position was further and gradually elaborated; it was a slow but geometric process, very skilled. Apparently, nothing had changed: the old Republic was always there, the magistrates themselves were in the eyes of everyone, but, in essence, Rome was ruled now by a monarch. This truly sublime ambiguity was Augustus' masterpiece, making him one of the greatest politicians of all times, if not the greatest, and allowing him to hold power firmly throughout his life.

Augustus also created a series of new administrative commands, with officials appointed directly by him who could be dismissed at any time, the "Praefecti". The Prafectus Urbis was in charge of the administration of the city of Rome; the Praefectus Annonae took care of the supplies of the town; the Praefectus Vigilis was the head of a department of "vigiles", police officers and firefighters. Finally, the Praefectus Praetorii led the “Praetorium”, that is, the emperor’s personal guard, composed of special soldiers called Praetorians. We’ll see how they will play a decisive role in the history of the empire.

The provinces were divided into two categories. The ones that did not require a military presence, which were firmly subject to Roman control and pacified, were administered by the Senate; thus, they were called “senatorial”. Sicily, for example, was one of them. The border provinces, or generally those not fully pacified yet, which required the stable presence of one or more legions, were placed under the direct control of the emperor, hence the denomination of “imperial”. Syria and the three provinces of Germany, for instance, were imperial provinces.

The army was the basis of the emperor's power. Augustus settled the veterans, distributing lands and later cash prizes at the end of their careers. After the end of the Civil Wars, he reduced the legions from 50 to 25; however, for the protection of the emperor himself, a special guard of 9,000 men, the Pretorians, was created, recruited from good Italian families. Military service became professional. After 20 years of service in the infantry and 10 in the cavalry, a soldier could be discharged and received a plot of land in a colony or a sum of money as a career-ending prize. The poorest citizens enlisted, attracted by the possibility of becoming landowners; but also the non-Roman inhabitants of the provinces, who thus obtained Roman citizenship, could enrol. This way, military service was separated from citizenship, a clear sign of the end of the Roman Republic. Thanks to it, ever larger masses of individuals were put in contact with the Latin language and the Roman-Greek culture, and the army became a powerful vehicle for romanization in the regions where the legions were based: the hope of achieving a superior social status through military service in the Roman army meant that for many non-Romans the legions of Rome were not a hostile presence but the guarantee of a better future.

Peace and stability boosted trade: the end of the civil wars brought an economic boom to Italy. Augustus restored and extended the road system and organized an efficient postal system. With the end of confiscations, many owners were encouraged to invest in their lands to increase agricultural productivity: agriculture was born again due to peace.

Thanks to the availability of great riches, Augustus and his family and collaborators financed the construction of a significant number of public works of various kinds. Thanks to Augustus and local benefactors in search of fame, monuments and public buildings rose everywhere in Italy and the provinces: arches, monumental access gates, aqueducts, arcaded streets, city walls, baths, theatres, amphitheatres.

Obviously, the sign of a new regime was more evident in Rome: new buildings and monuments were erected in every public space of specific importance, the tangible testimony of the power and the generosity of Octavian Augustus and his range of relatives and acquaintances. In the Roman Forum, the symbolic centre of the ancient Republic, various buildings were erected to mark the centrality of the Gens Iulia, the emperor’s family, in the State: the temple dedicated to Divus Iulius, that is to Caesar deified, the new Curia, then called Iulia, already begun by Caesar, the columns for the victories against Sextus Pompey and at Actium, an arch for the victory over the Parthians.

Next to the ancient Roman Forum and the Forum built by Caesar, Augustus erected his own Forum. The squares, buildings, structures of the traditional Forum (today conventionally called Roman, on the right of the road leading from Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum) were now inadequate for a city of almost one million inhabitants, the most populated in the world at the time. Augustus expanded Caesar's design, flattening the slopes of the Quirinale hill beside the area: a colossal work, at the end of which he would erect a formidable wall, 33 meters high, which served both as containment and a separation between the public area of the Fora and the plebeian district of Suburra with its prostitutes.

Augustus had cast a vow before the Battle of Philippi: if he won the battle against Brutus and Cassius’ army, he would dedicate a temple to Mars. Thus, the temple, the Augustan forum's ideal centre, was dedicated to Mars Ultor, the Avenger. Today we can still admire the white shade of the Carrara marble that was used for the temple, and the coloured marbles from Africa, Greece and Asia Minor decorating the floor of the Forum: the use of marbles from every corner of the empire aimed at stunning the visitor aesthetically, but more than that it was the tangible evidence of the universal power of Augustus and, through Augustus, of Rome. The temple was not only a devotional place but also a shrine of Roman glory. Caesar's sword was kept there, together with the Roman insignia that consul Crassus had lost against the Parthians in 53 BC. and that had been recovered by Octavian. In a square room next to the temple, a colossal statue of Augustus was placed: only the footprints of the feet remain, seven times the standard size. Trials and meetings were held in the Forum and inside the Basilica Iulia, and their arcades provided shelter for commercial activities.

On the Palatine Hill, for the victory of Aktios, Octavian had a temple dedicated to Apollo, built next to his palace, thus emphasizing his connection with Apollo, the God of victory and harmonious pacification. Next to the temple of Apollo, two libraries, one Greek and one Latin, were erected. The buildings will be the first nucleus of the imperial palaces, and in fact, "palace" comes from "Palatium", the name of the Palatine Hill.

The faithful Agrippa commissioned a new bridge on the Tiber, two new aqueducts and the first great public baths in Rome; he also had the Pantheon built, the temple to all the gods, which we can still admire today, although not in the original shape (the temple was almost entirely rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD). Carrara marble was widely used, and Augustus boasted: “I have received a Rome of bricks, I will leave a Rome of marble”.

Everything aimed at highlighting Augustus’ respect for the most genuine Roman tradition and the religion of the “Patres”, the ancestors. Augustus wanted the buildings he built or the works of art he commissioned to be the tangible representation of the return to the authentic Roman spirit, sober and moderate.

The works of art of the Augustan age are opposed to Hellenistic art's overabundant passions and emotions. Their style must express the return to order after the moral disorder of civil wars: for this reason, they are inspired by the Greek art of the classical age, that is, of the 5th century BC, the highest and most noble times of the Greek culture. However, just because the return to tradition is directed from above, today Augustan art can appear elegant but also cold and detached.

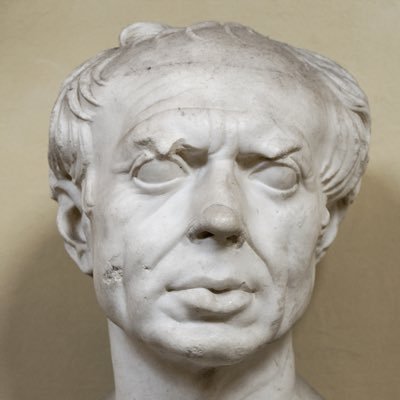

The most remarkable manifestations of Roman art are the portraits, which realistically transmitted the features of the ancestors to future generations, and the great public works. As the State's interests prevailed over the ones of individual citizens, it is difficult to remember the name of an artist or an architect. In fact, Roman art is anonymous for the most part. Most of the works, infact, are remembered with the name of the consul under whose consulate they were executed, or the emperor or the client who promoted its realization or to whom they were dedicated. So, for example, we talk about Claudius’ Aqueduct, Titus’ Arch, the Flavius Amphitheater (the Colosseum, built under the emperor Flavius Vespasian), Maxentius’ Basilica, Caracalla’s Baths.

Speaking of Roman construction techniques, Roman architecture is characterised by the use of the arch and the vault. They allowed the Romans to cover immense spaces, also using powerful construction machines (nothing more than war machines converted to civilian use). To build buildings with vast vaults and domes, Romans mostly used concrete, a compound made of lime, sand, gravel or small irregular scales of stone or brick, and water, to which they often added bricks. After the slow evaporation of water, and following chemical reactions, this material turned into blocks with the same consistency and resistance as the stone. It was not very different from the concrete used today in construction, and thanks to it, the Romans could build buildings with vaults and domes that still defy time.

For the Romans, the community was always more important than the individual, and the State was above all. In Roman society, therefore, the great public works, civil and military, were significant. These included roads, ports, bridges, aqueducts, sewers, and various collective interest buildings such as archives, warehouses, markets, thermal baths, basilicas used for the administration of justice, business and public meetings.

Roads linked Rome to the other cities of the Italian peninsula and, subsequently, to those of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Roman road was on average 3 meters wide and consisted of at least three layers for a depth of about 150 cm. The lower layer consisted of a set of pebbles, the middle layer of a mixture of sand and gravel, and the flooring of rounded pebbles or slabs of stone. You can still see a long section of a Roman Road in the Appia Antica Park, just outside Rome; the Appia Antica originally ran from Rome to Brundisium in Puglia.

Another typical Roman artefact is the aqueduct. Water supply was vital for Rome and all the cities of the provinces. As many as 11 were built in Lazio between 312 BC and 206 AD to bring water from distant springs to the heart of the capital. The most spectacular is the Aquaeductus Claudius, built between 38 and 52 AD by the emperors Caligula and Claudius; it was about 70 km long, and for almost 20 km, water ran on arches supported by tall, robust pylons that still rise in the calm Roman countryside, relevant signs of the landscape.

In general, the relationship between Romans and art was quite problematic. They were more interested in concrete issues than in abstract ones. Their disposition, hard and sober, had been defined over centuries of almost uninterrupted wars. Artistic and philosophical discussions, so beloved by the Greeks, were considered a waste of time and useless otiosity. They could only lead to the relaxation and softness of customs and to abandoning the traditions which had made the city the ruler of the world. Even the objects the Romans surrounded themselves with, especially in the Republican age, were made of poor materials and roughly finished.

It was the exceptional flow of immense riches from the cities and the temples Romans predated that forced and got them used to a new relationship with art. (we will talk about it in the next episode). After the conquest of Southern Italy, precious metals and money flowed into Rome from several cities. Many Hellenistic works of art were brought from Syracuse after its defeat in the 1st Punic war. Finally, the definitive conquest of Greece in 146 BC put Rome into direct contact with its classical art.

The concentration of art treasures in Rome and the increasingly frequent contact with very different peoples encouraged collecting. Everything with a value, because it was rare or unique, made with precious materials, or executed by a well-known Greek master, was considered worthy of being amassed in the temples of Rome or displayed in the mansions of the Patricians and Equites. But, despite this, the Romans, linked to the cult of ancestors and the rules transmitted by tradition, always felt uncomfortable as art experts.

In the 1st century BC, Rome was invaded by individual statues and statuary groups, original or in copy, the result of spoils of war but also bought from flourishing Greek and Asian artisan shops. Many sculptors from the East moved to Rome, to that city that was beginning to shine with its own light in the centre of the Mediterranean. And here they opened flourishing workshops, producing new works or copying the great Greek originals, which in this way have come to us, thus allowing art lovers of all times to appreciate the Greek sculpture in all its grandeur. After almost 2 centuries, Greece had won the battle of culture!

When Octavian returned to Rome in 29, laden with the riches of Egypt, he was the undisputed master of the State. His victory was total and not only on a military level: he had won in the minds of the Romans too. In fact, after decades of civil wars, proscriptions, massacres, plots, dangers and confiscations, many were genuinely convinced that all this was the inevitable consequence of the Republican order. Peace under the power of one seemed preferable to the chaos of war and destruction, a result of the endless disputes among political factions led by individuals who used republican offices and legions as instruments of their power struggle.

Romans demanded order, peace, security, good administration, a healthy currency, and their goods' protection. And Octavian set out to guarantee them. He won the favour of the soldiers with cash, the support of the populace with abundant food, and the backing of all Romans with the sweetness of peace. And so he gradually began to impose himself, to merge the functions of the Senate, the magistrates and the laws in one person, himself. And no one opposed to it.

Using the Egyptian gold, he dismissed most soldiers (the army had risen to a total of 500,000 men), giving veterans some land he bought on purpose to turn them into peasants. He kept 200,000 in service, and he proclaimed himself emperor, a purely military title; and he started great public works. Now, he faced a much more difficult task: how to consolidate this immense power and, on the other hand, how to avoid the tragic end of great political figures such as Pompey, Caesar, Anthony, the victims of their greatness.

First of all, he should avoid a mistake that had been fatal to all of them: the history of the Roman Republic, and the same deadly accusation made by the enemies to Julius Caesar, taught that he should never pronounce words as “king” and “kingdom”. For over five centuries, that is, since the monarchy had been abolished and the Republic established, for a Roman politician, the only suspicion of aspiring to a kingdom led to political and often even physical death, the very murder of Julius Caesar taught him so. But how was it possible? This was the big problem: things needed to be changed because it was clear that the old Republic was now exhausted, worn out, but how was it possible to change things without switching to a fully declared monarchical regime?

The path followed by Octavian is a subtle and brilliant game with words: change everything, making people believe that nothing changes. The Roman ideology was the opposite of the modern one, contrary to change, to new things. A politician who made novelty his slogan would have committed suicide, and not just politically. The best of history was behind them; it was on the side of the ancestors, it was “mos maiorum”, the customs of the ancient heroes, the golden age.

Even counting on the desire for peace, Octavian could not simply proclaim himself king or dictator: the story of Caesar, who had been murdered on the charge of having aspired to the kingdom, was a clear sign that Romans would not accept a real monarchy. Octavian understood this, and he presented himself not as a ruler but as the one who restored legality and gave the power back to the Senate and to the popular assemblies after the chaos of the civil wars.

He had the extraordinary ability to carry out a revolution giving the impression of restoring tradition. As Octavian himself recalls in the “Res Gestae”, his political autobiography, 27 BC was the decisive year. At the Senate session on January 13th, Caesar's son declared that he wanted to return all his powers to the Senate; he proclaimed the restoration of the Republic and announced that he wanted to retire to private life. The Senate responded, in turn, by begging him to assume all the powers and giving him that name of Augustus, which literally meant "the enhancer". And Octavian agreed to it, whimsically. It was a scene perfectly recited by both sides, and it showed that the conservative and Republican obstruction was over: even proud senators preferred a master to chaos.

Augustus, a fateful word, an exceptional idea. The title of Augustus, worthy of reverence, had no real effects, but it was not just a symbolic homage; it had an almost sacred value: Octavian, although formally a magistrate like the others, was put on a level of higher authority.

The title of Augustus became an integral part of Octavian’s name, from which it passed to the following emperors. But Augustus' title was only a step in the construction of absolute power, always complying formally with the law. He also became "princeps Senatus", prince of the Senate, the first, once again a subtle masking of reality. Thanks to this perfectly legal position, Octavian was the first to cast his vote, influencing the vote of all other senators. The term, which had no legal value, suggested that “Augustus princeps” was only the most authoritative of the citizens of a republic officially still alive, not the lord of a mass of subjects without rights, as he was in reality.

Octavian himself states that from that moment, that is from 27, he had a “potestas”, we can translate a little inaccurately a “power”, equal to all those who were his colleagues in each judiciary office. He acknowledges, however, that he had a superior “auctoritas”, a prestige deriving from his exceptional merits, from having extinguished civil wars and saved the Republic. In other words, he acknowledged that he had only a “charismatic” superiority, a very skilled statement to which countless essays have been dedicated.

To celebrate the peace and concord he brought to the state, Octavian Augustus even invented a goddess, Peace. He dedicated to her a temple, which was also a self-celebration of his own role as peacemaker and defender of the faith. It is the Ara Pacis, the altar of Peace, which we can still admire today on the banks of the river Tevere, next to the Mausoleum of Augustus.

The Ara Pacis was built between 13 and 9 BC, and it was initially placed right in Campus Martius, the area traditionally dedicated to the god of war, where the rites propitious for military campaigns were celebrated. The monument consists of an almost square marble enclosure surrounding a monumental altar, accessible through some steps, and is decorated with plastic reliefs. In the enclosure, there are two entrances, which allow you to enter, turn around the altar and exit from the opposite side.

Augustus' political and cultural message is carved onto the outer upper band of the monument. Here are a dedicatory procession and two scenes that refer to the foundation of Rome (Romulus and Remus lactated by the wolf, Aenea sacrificing to the gods) and two symbolic representations, the goddess Rome sitting above a pile of weapons and the goddess Tellus holding the twins, flanked by the personification of air and water. The characteristics attributed to Tellus – animals and fruits – indicate the birth of a new golden age for the earth. This relief, therefore, is intended to reinforce the idea of happiness associated with fertility and prosperity.

The scene of the wolf recalls the divine origin of the founder, Romulus: the twins fed by the she-wolf are, in fact, according to tradition, children of the god Mars and the vestal priestess Rea Silvia. The presence of Aeneas is a clear reference to Gens Julia, the "family" of Octavian; Aeneas, like Augustus, is a pious man, respectful of his ancestors, and he presents himself with a veiled head. The allegorical figures of Rome and Tellus allude to the fate of the Empire: Rome founded its power on military force, but now it is time to govern with justice and peace over all other peoples and above the elements of nature.

In the procession, together with the most important priests of the Roman state religion, all members of the imperial family, including women and children, even the acquired members of the family are depicted. The characters could be easily recognized by the Romans, who saw their portraits in statues and coins. In the lead is Augustus; then Marcus Agrippa with his son Caius Caesar, Julia (Augustus’ daughter, the wife of Agrippa), Tiberius, Antonia Minor (the daughter of Mark Anthony and Octavia, Augustus’ sister) followed by her son Germanicus and facing her husband Drusus (Tiberius’ brother). The proportions of the draperies are strictly classic, although the way in which the figures are grouped is more naturalistic than the one of the procession on the frieze of the Parthenon in Athens, from which the one of this altar derives.

The Ara Pacis is truly the monument that most exemplifies the role that Augustus is building for himself: Father of the Fatherland, second founder of Rome, the one who carries out Rome's mission to unify the known world, according to the model of Roman civilization. From the Ara Pacis, an idea spreads across the Roman world: Augustus is destined to be welcomed among the gods, and he and the emperors after him must be revered as gods.

For several years, from 31 to 23 BC, Octavian retained power by being repeatedly elected consul; at the same time, he maintained control over numerous provinces and the legions stationed there. But he was aware that it was a temporary accommodation. The solution was found in 23 BC: Augustus ceased to hold the annual office of consul and was given for life, directly, the two powers that would allow him to manage the state, untying them from the offices connected with them.

The first was the “tribunicia potestas”, the power of the tribune; thanks to it, he had all the powers of the tribunes of the plebs: he could convene the Senate and the people's assembly, present bills, above all he could veto any decision of the Senate and other magistrates and had the right to force anyone to obey his orders and to punish those who did not comply. So, all in all, nothing could be approved without his consent. The second was the proconsular command, with powers greater than the other proconsuls’ and no time limit; by this, Augustus retained the title of “imperator” and thus the army's control.

Formally the Republic, with its magistrates, the Senate and the popular assemblies, remained alive. Still, everything was designed so that the supreme power was in the hands of an individual to whom the Senate and the people themselves had formally attributed a series of prerogatives. Senators and members of senatorial families still occupied the offices of the Republican tradition: questura, pretura, consulate, but these offices were increasingly devoid of real powers, because their administrations were run by officers nominated by the emperor. The popular assemblies were utterly deprived of effective power: and though they were not eliminated, they were reduced to formally approving decisions already taken elsewhere. The election of magistrates by the rallies followed the emperor's directions, and only the laws proposed by him could be passed.

In foreign policy, Augustus pointed not so much to the mere conquest of new territories to attain military glory or loot, but instead, he aimed at stabilizing the regions already subject to the Romans and bring the frontier forward to coincide with easily defensible natural borders, such as the Rhine and the Danube rivers. The Alpine valleys were conquered, both south of the Alps (the Aosta Valley) and north (the Noric, present-day Carinthia in Austria, and Rhaetia, the Swiss valleys). Pannonia (eastern Austria and Western Hungary) was also conquered; looking at a map, we can see that the goal here was to secure the Danube River as a stable border of the empire. To protect the Danube border, he ordered to move forward into Germany to the Elbe River. Thus, the empire's northern boundary would be on the Elbe -Danube rivers line. Between 12 and 9 BC, Germany was submitted by Drusus, Augustus’ stepson: it seemed it would become Roman; apparently, the Germans accepted Roman rule, as it had happened in Gallia.

The situation in the region was relatively peaceful; Romans were already founding new cities there, as they had done elsewhere in the Empire; Germans and Romans were beginning to mix up in markets and fora. But the fire was smouldering under the ashes. In 9 AD, a revolt of the Germans broke out, led by the head of the tribe of the Cheruscans, Armin: he had fought in the Roman army in previous campaigns, he had even obtained Roman citizenship, and his full Roman name was Gaius Julius Arminius.

Armin, presumably an officer in the Roman army, had plotted against the Roman governor Publius Varus. Varus was informed of the plot but refused to give credit to it and set out to put down a revolt of which the conspirators had warned him.

The Roman army led by Publius Varus recklessly entered the deep forest of Teutoburg, and three legions were massacred there. The historian Dionis Cassius recounts that, when Augustus knew what had happened to Varus, he tore his clothes and kept on shouting: "Varus, give me my legions back". He expected the barbarians to march against Italy and against Rome itself, but it did not happen; the Germans of those times did not have any desire to defy the Roman power outside their territory.

Varus' defeat marked a turning point in the history of Europe: Germany was never conquered again by the Romans, and the Rhine became the border between a Latin Europe and the lands where the German language is still spoken today. The Germanic populations will never be submitted and will remain over the centuries a constant threat to the empire until its collapse under the pressure of barbarian invasions.

In the East, Augustus pursued a different policy, aiming to gain Roman supremacy through diplomacy. He entered into negotiations with the Parthian king, and he succeeded in placing a friendly king on the Armenian throne. Still, above all, he obtained the return of the Roman military insignia captured by the Parthians in the wars against Crassus and Anthony. Rome obtained the control of several small regions of the East through allied kings, such as Herod of Judea, under whose reign Jesus of Nazareth was born. These small kings were totally submissive to the Roman will: Augustus even decided their family policies and their succession.

Augustus is one of the greatest political myths in the West. But, despite his fantastic fortune, the figure of Augustus does not arouse the same emotions, the same passions, the same involvement of Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar. Why?

Basically, Augustus’ life was an extraordinary human and political adventure but poor in events that can be translated into literature, theatre, cinema. Usually, Augustus enters the movies or the books obliquely, either because of the evocative story of Anthony and Cleopatra or because of the murder of Caesar, often drawing inspiration from Shakespeare. Then, the great losers, the unfortunate heroes, appear to us more fascinating than the great winners. There is a lot of charm in the sudden death of Alexander the Great, eliminated at the age of 33 by a sudden fever when he had conquered most of the world known to the people of his times, or in the assassination of Julius Caesar, pierced by daggers in a conspiracy that hundreds of people in Rome knew but of which he was unaware. In short, the winners who die old in their bed, like Augustus, who died at the age of 77 after more than 40 years of reign, do not have the same charm.

Notwithstanding this, the age of Augustus is undoubtedly one of the happiest times in Roman history, thanks to his smart choices, his incredible ability to choose the times of political action and to gather consensus around his figure. Caesar’s life and death may be more intriguing, more dramatic, but Caesar did not survive his creature. Octavian did, and made it stronger and more alive. Thanks to him, Rome will be the beacon of the western world for another 400 years, and its influence will extend well beyond the end of its Empire.

Episode 11 - Octavian and Anthony, the final round

Written by Marcello Cordovani

In 40 BC, Octavian and Anthony had confronted each other in Brindisi with their armies, without clashing; instead, they had renewed the triumvirate alliance, including once again Lepidus. They agreed to divide the Republic's territories among themselves, without any significant protest by the Senate or other magistrates: Octavian had Europe, Lepidus Africa, and Anthony chose Egypt, Greece and the Middle East. A marriage even sealed this agreement: Anthony married Octavia, Octavian's sister.

The following year, in 39, the triumvirs made an agreement with Sextus Pompey, the general's son, who had recruited a fleet of exiles, proscribed, former slaves and pirates; with them, he had occupied Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, and hindered grain supplies from Sicily and Egypt to Rome. In exchange for renouncing such piracy actions, he was guaranteed the government of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and Acaia (that is, the Peloponnesus, in Greece).

But this agreement was short-lived. Sextus Pompey, having not received the province of Acaia, decided to resume his piracy actions: in 38, therefore, the triumvirs chose to eliminate him, this time permanently. The decisive naval battle took place in 36 near Milazzo, in Sicily: the fleet of the triumvirs, led by General Marcus Agrippa, a peer and a friend of Octavian, defeated the one of Sextus Pompey, who fled to Asia and later was killed there. With him, the last member of the factions linked to the Republican system was eliminated.

A few weeks later, Lepidus, who had brought his troops from Africa to Sicily to fight against Pompey, and was not happy about his subordinate role in the triumvirate, attempted to regain some weight and rebelled against Octavian. But Octavian was clearly too strong for Lepidus, and Lepidus’ soldiers knew it. It was enough, for Octavian, to show up at Lepidus’ camp, alone and unarmed, as Caesar, son of Caesar! And Lepidus' troops instantly passed on his side: Lepidus had his life saved and retired to private life in a splendid villa at Circeo. Having cleared the fleet of Sextus Pompey and neutralized Lepidus, Octavian was now the absolute master of Italy and the western provinces.

On November 36, Octavian returned to Rome and celebrated his triumph. The Senate granted him the inviolability for life, a prerogative of the tribunes until then, and the right to wear the laurel wreath, as Caesar already had done before him.

Now, what was Mark Anthony doing in the meantime? In 41, at the time of his first voyage to the East, after the victory in Filippi, he had ordered Cleopatra, you remember, the charming Queen of Egypt, Caesar's lover, to meet him in Tarsus, in Greece.

Anthony remembered her as a young girl, he had met her a few years before in Alexandria, but he had not seen her since. That day, Cleopatra arrived at the meeting determined to assert all her skills as a seductress. She showed up on a ship with red sails, the crew was composed of servants dressed as nymphs, and she was dressed in a provocative Venus costume. When he saw her, Anthony was stunned. Now he understood why even Caesar, who had had so many women, had been bewitched by her. He could not resist her. They went together to Alexandria, and here the refinement, the luxury of the life with Cleopatra conquered him, who had lived a soldier’s life until then.

Behind Anthony’s decision to embark the army and confront Octavian in Brindisi in 40, there was probably Cleopatra. And when Anthony returned to the East in 39, he was a married man and none other than Octavian’s sister, Octavia. But, regardless of his bond in Rome, Anthony resumed his relationship with Cleopatra and began to live permanently with her at the Court of Alexandria. In fact, he even married her!

The marriage between a Roman citizen and a foreigner was invalid under Roman law; in any case, it was an affrònt to Octavia, his legitimate wife and Octavian's sister, who had remained in Rome with their two children and was pregnant for the third time. It was easy for Octavian to present Anthony as an individual who, overwhelmed by his passion for a corrupt foreign woman, failed in his duties as husband and father. But it was not the only fault in the eye of the public opinion in Rome.

In 36, Anthony organized a great expedition against the Parthian empire, the only adversary powerful enough to contrast Rome: you probably remember that 17 years earlier, in 53, the Parthians had annihilated Crassus' army in Carre. Now, taking advantage of the chaos of the civil wars, the Parthians had occupied much of Syria and Asia Minor (that’s present-day Turkey). Anthony hoped to achieve a final, definitive victory against the only real opponents of Rome, which would bring him eternal fame and popularity.

The expedition was the biggest ever organized by Rome: 60,000 infantrymen, 10,000 cavalrymen, another 30,000 troops provided by the kings of the kingdoms of the area allied to Rome. But it had started late in summer; Anthony ran unnecessarily behind the enemy for 500 km, leaving behind the siege machines that were intercepted and destroyed by the Parthians. The city where the king's family lived resisted the siege, so that in autumn, Anthony couldn’t help but retreat. The loss of food and the continuing attacks by the Parthians turned the retreat through hostile land into a disaster, with the loss of 1/4th of the troops.

Despite his disastrous retreat, in 34 Anthony offered himself a solemn triumph in Alexandria, scandalizing Rome, and married Cleopatra, giving the whole Middle East as dowry to her two sons. Caesarion, the son of her and Caesar, was proclaimed crown prince of Egypt and Cyprus. Anthony then sent a divorce order to Octavia: thus, he was breaking the only bond that still tied him to Octavian.

Anthony now acted as if the eastern provinces had been his private property: it seemed that he wanted to transform the rule of Rome into an oriental monarchy, with its capital in Alexandria. Also, he recognized the son he had had from Cleopatra as legitimate and gave him the name of Alexander: a Greek name, not a Roman one, that is, the name of that Alexander the Great, from which the oriental kingdoms originated.

Attracted by the dream of an oriental monarchy, Anthony had lost contact with Rome: the public opinion now favoured Octavian, who proposed himself as the defender of the genuine Roman tradition. Anthony now looked like a puppet in the hands of the beautiful, corrupt and corrupting queen of Egypt.

Octavian was a master of communication, with a modern but inappropriate term we may say he was a master of propaganda. Romans always painted the East as a place of corruption, sensuality, excesses. And Octavian had an excellent game presenting himself as the champion of pure Roman and Italic values, then East versus West, Italy against Egypt.

By the year 32, the powers of the triumvirs, ten years after 43, had expired. Each of the two contenders was preparing for open war, but neither wanted to be attributed the responsibility for the outbreak of hostilities. Octavian then appeared in the Senate, surrounded by a group of soldiers and armed friends, to defend himself against his opponent's accusations. Actually, it was a coup d'état, but carried out without violence; Octavian wanted to appear only as a political leader, eager to defend his reputation. And the two Consuls, who favoured Anthony, helped him by leaving Rome. Octavian did not have any more adversaries on the Roman political scene.

Since then, Octavian exploited every move Anthony made to throw mud on his conduct, to present him as the traitor of Rome. Even some of Anthony's closest followers preferred to pass on Octavian's side. The former consul Lucius Plancus revealed to him not only Anthony's plans but also the contents of his will and who had been entrusted with it.

It was an unexpected gift for Octavian. He quickly found the will, which was in possession of the Vestals, the priestesses of Vesta, seized it and took it first to the Senate, then to the people's assembly, where he had it read. In it, Anthony solemnly stated that Caesarion was the true son of Caesar; thus, he wanted to overshadow Octavian, who was only the adopted son of Julius Caesar. Also, Anthony designated the sons he had from Cleopatra as his only heirs, and Cleopatra herself as regent. Finally, wherever he died, he was to be buried in Egypt!

The document was most likely a fake, but it confirmed all the suspicions that most Romans had towards this intriguing traitor and allowed Octavian to banish a war. A war that he, very perceptively, declared not to Anthony but to Cleopatra: the conflict was presented as if it was directed against a foreign power and not as a new civil war; Anthony was portrayed just as a traitor, subject to the queen of Egypt.

The two opponents prepared for the fight. Although not in any official position, Octavian obtained the oath of allegiance and, therefore, funds and troops from Italy and the other western provinces. On Anthony's side were Asia Minor, Greece, Macedonia, Thrace, Cyrenaica, the Egyptians and numerous kings and princes of states bordering with Roman rule in the East.

Octavian's propaganda was very skilful at presenting the war as the clash between the Latin and Latinized West, morally healthy, the faithful guardian of tradition, respectful of the Republic, and the Greek and barbarian East, refined but corrupt.

It was a sea war. The two fleets clashed at Actium, in northwestern Greece, on September 2nd of the year 31 BC. Octavian’s navy, led once again by Marcus Agrippa, though inferior in numbers, succeeded in routing Anthony and Cleopatra’s fleet. Cleopatra fled with her naval team even before the battle was definitively lost, and Anthony followed her with some ships. It was a huge mistake because the 19 legions on the ground, camped around Actium, were not even engaged in a battle.

Octavian did not chase the fugitives right away. He knew that time worked for him and that the longer Anthony stayed in Egypt, the more he burned out. He landed in Athens to restore order, then crossed Asia to dismantle, one by one, all of Anthony’s alliances, isolating him, and eventually moved to Alexandria. On the way, he received three letters: one from Cleopatra, promising submission, and two from Anthony, asking for peace. To him, he did not answer; to her, he let her know that he would leave her on the throne if she killed her lover.

When Octavian arrived in Alexandria, he locked the city. The next day, Cleopatra's mercenaries surrendered. Anthony received news that the queen had died; he believed it and suicided. But Cleopatra was alive, and she asked Octavian for permission to bury Anthony’s corpse and be granted an audience. And Octavian agreed. She presented herself to him as she had done with Caesar and Anthony: scented and cloaked in veils. But, under those veils now, there was a 40-year-old woman, not a 29-year-old girl, at the top of her charm. Octavian was much younger than her, not like Caesar or Anthony, and he did not need to resort to a great strength of character to treat her coldly: he announced that he would take her to Rome and she would walk as an ornament of his chariot during his triumph. Cleopatra felt lost, and this drove her to suicide; she had herself poisoned by the bite of a snake.

Octavian treated the dead with a touch from which we can reconstruct his character. He allowed the two corpses to be buried next to each other. In the meantime, to avoid any misunderstanding, he sent the sons of the two to Octavia, his sister, who raised them as if they had been her own; he had Caesarion killed, to get rid of a possible rival, and proclaimed himself king of Egypt, so as not to humiliate it by declaring it a Roman province, but also to make it his private property and pocket its immense treasure.

At that time, Octavian was just 31; he was the only and absolute heir of Caesar and the owner of the Roman State! Finally, the civil wars were over; with them, not formally but certainly in fact, also the history of the Roman Republic had come to an end!

Did Caesar want to be king? We will never know. Maybe he did not know it himself. But his adversaries were sure of it, and an episode confirmed their conviction.

It’s February 15th, 44 BC. It’s the day of the Lupercalia. Lupercalia was one of the most ancient festivals in Rome. It was held each year on February 15th, and it was a bloody, violent and sexually charged celebration: animal sacrifices, random matchmakings and couplings, in the hopes of warding off evil spirits and infertility. Lupercalia was to honour the she-wolf at the origin of Rome and please the Roman fertility god, Lupercus. The rituals traditionally took place on Palatine Hill and within the Roman open-air.

The festival began with sacrificing one or more male goats, symbols of sexuality and fertility, and a dog by priests called Luperci. Afterwards, the foreheads of two naked Luperci were smeared with the animals’ blood using the bloody, sacrificial knife. After the ritual sacrifice, the feasting began, and when it was over, the Luperci cut strips of goat hide from the sacrificed goats and then ran naked (or nearly naked) around the Palatine, whipping any woman within striking distance. Many women welcomed the lashes and even bared their skin to receive the fertility rite. Over time, nakedness during Lupercalia lost popularity. The festival became more chaste, and women were whipped on their hands by fully-clothed men.

In the late 5th century AD, Pope Gelasius I prohibited the pagan celebration of Lupercalia and declared February 14th the day to celebrate the martyrdom of Saint Valentine instead. However, it’s improbable he intended the day to commemorate love and passion. But Valentine’s Day is not the only festival that presumably comes from the Roman Lupercalia; even the Carnival draws some aspects from these celebrations, such as chaos and purification.

During the festival, Caesar watched the ceremony on his golden seat in triumphal attire, and Mark Anthony was one of the participants in the race. When Anthony entered the Forum, and the crowd opened before him, he handed Caesar a tiara intertwined with a laurel wreath. There was applause, not roaring but subdued, as if it was prepared. Caesar rejected the crown, and all the people applauded; when Anthony again offered the crown, a few applauded, and again, everyone applauded when Caesar rejected it for the second time.

Seeing these things, the supporters of the republican tradition decided that it was time to take action; they were also encouraged by the seemingly hostile reaction of the people. The plot was cloaked in noble ideals: they said they wanted the death of a tyrant who aspired to the crown, to share it with Cleopatra, then leave it to the bastard Cesarion after moving the capital to Egypt. Had he not erected a statue of himself next to those of the old kings? Hadn't he had his face engraved on new coins? Power was very tempting, and it was better to kill him before he destroyed Rome's freedom and supremacy.

At the beginning of March, the two leaders of the conspiracy, Brutus and Cassius, were informed that at the next Ides, that is, the 15th, Caesar would make the extraordinary announcement. His lieutenant Lucius Cotta would propose to the assembly to proclaim him king because the Sibylla had predicted that only a king could defeat the Parthians, and the popular assembly would approve, of course. The Senate also would approve: Caesar’s recent reform had given the Caesarians a majority. So, the dagger was all that remained before it was too late.

On the morning of the Ides, the 15th of March, while Caesar was dressing up for attending the session of the Senate, his wife Calpurnia told him that she had dreamed of him covered in blood and begged him not to go. But a friend who belonged to the conspiracy came instead to urge him, and Caesar followed him. On the street, a fortune-teller shouted out at him: “Caesar, beware of the Ides of March”; "It’s already the Ides", he replied, "but they are not over yet!" the other said.

At that time, the Senate courtroom was situated outside the Forum, in a building called “Pompey’s Curia”, the area in the centre of Rome has been preserved and is now called Largo Argentina. When he entered, someone put a rolled papyrus in his hands: it was a detailed complaint, but Caesar did not have time to read it. Right after that, the conspirators were all over him with their daggers.

The only one who could defend him, Mark Anthony, had been stopped in the anteroom by Trebonius, a conspirator. Brutus himself had given instructions to keep Anthony away from the scene of the murder, to spare his life. Caesar first tried to shelter with his arm, but he stopped when, among the assassins, he saw Brutus. Suetonius reports that his last words were: "quoque tu, Brute, fili mi", " You too, Brutus, my son", and it’s probably true. He fell, pierced with blows at the foot of the statue of Pompey.

Anthony finally entered the room, he saw the corpse lying on the ground, covered with blood, and everyone expected him to have an outburst of wrath. Instead, the faithful lieutenant fell silent and left. Outside, a crowd grew; the news had already begun to circulate. Fearfully, the conspirators showed themselves on the door, and some of them tried to explain what had happened, justifying it as the triumph of freedom. But the crowd was more and more menacing. The conspirators retreated, they barricaded inside the Capitol, and they sent a message to Mark Anthony to come and get them away.

Anthony came the next day and managed to calm the crowd with a skilful speech in which he asked for the order to be maintained and, in return, he promised that the guilty would be punished. Then he went to Calpurnia, who was annihilated by grief, and had her give him Caesar's will, sealed in an envelope. He handed it over to the Vestals, the priestess of the goddess Vesta, as was the use of Rome, without opening it, so much so that he was sure he would be designated as heir. Right after, he secretly sent to call the troops camped out of town, then he returned to the Senate, and here he delivered a speech, in which he approved the senators' proposal for general amnesty as long as the Senate ratified all projects that Caesar had left incomplete. He also proposed to Cassius and Brutus a governorship that would allow them to leave Rome, and on that evening, he kept them with him for dinner.

On the 18th, Anthony was charged with funeral praise. This was the gravest mistake made by Brutus: earlier, he had left Anthony alive, now he allowed Caesar's funeral honours to take place the way Anthony desired; he had lost control of the situation if ever he had any. The next day, Anthony had the Vestals deliver Caesar’s will; he opened it solemnly before the high offices of the State and gave a public reading of it. Of his private, enormous fortune of about 100 million sestertii, Caesar left a small sum to every Roman citizen and donated his beautiful gardens to the city as a public park.

A great, heartfelt regret took the citizens for their benefactor. When the body was brought into the Forum, Anthony gave the eulogy and seeing that his words moved the crowd, he pathetically grabbed Caesar's robes, soaked with his blood, showed them high, showed the gashes produced by the daggers, all the wounds that Caesar had received. And the ceremony degenerated into chaos.

Caesar had reserved a bitter surprise for Anthony. The rest of the estate was to be divided among his three great-grandchildren; one of the three, Caius Octavius, was adopted as a son and designated as heir. The faithful lieutenant, who had invited the murderers to dinner just 48 hours after the murder of his boss, was thus rewarded for his strange fidelity.

The conspirators were not capable of devising a coherent political action, which would give them the support of the urban populace and Caesar’s veterans, and within a few days, they resolved to abandon Rome. In the following weeks, Anthony proclaimed to follow Caesar's notes and imposed the approval of numerous laws and ordinances favouring soldiers, friends, allies, subjects of the provinces.

In Rome, no one knew this Caius Octavius. His grandmother had been Julia, Caesar's sister. His father had made a decent career and ended up governor in Macedonia. The boy had grown up under an almost Spartan discipline and had studied profitably; uncle Caesar had no legitimate children, despite all the wives he had had, and he had taken Octavius into his house and had become fond of him.

In 45, Caesar had taken Caius with him to Spain when he had gone to eradicate the last followers of Pompey. On that occasion, he had admired the willpower of that young man, fragile in facing labours disproportionate to his health but with such courage in facing the enemy. Caesar had followed his studies and, when Caius was 17, he had entrusted him with a small command in Illyria, to practice militia and leadership. Octavius was still in Illyria when a messenger reached him at the end of March, with the news of the death of his uncle and his will.

He ran to Rome and went to see Mark Anthony: the general treated him with contempt, calling him "little boy". Caius did not take it as an offence, and in return, he calmly asked if the money Caesar had left to citizens and soldiers had been distributed. Anthony replied that there was something more urgent to think about.

But Caius did not lose heart. He contacted the wealthy friends of Caesar, borrowed the funds and had them distributed, as Caesar had ordered. Thus, he gained the favour of Caesar's plebeian followers and veterans, who began to look sympathetically at the “little boy”; even though he was very young, he knew how to behave. Moreover, thanks to the adoption, Caius had now taken the name of Caius Julius Caesar Octavius, a clear reference to his uncle.

Anthony was irritated, and a few days later, he claimed that he had been the victim of an attack and he had heard from the hitman that Octavius had organised the attack. Octavius asked for evidence, and since Anthony could not present it, he reached the two legions he had recalled from Illyria, joined them with those of the two consuls in charge and marched with them against Anthony. He was 18, at the time.

The Senate was on Octavius’ side. The aristocrats were alarmed by Anthony’s bullying: he had plundered the treasure, had arbitrarily occupied Pompey's palace and appointed himself governor of Gallia Cisalpina so that he could hold an army in Italy. The Senate realized that by letting him act freely, soon they would end up with another Caesar, and worse than the original one. And for this, they decided to favour Octavius, a boy they thought they could manoeuvre more easily.

Feeling that he was losing support in Rome, Anthony fled to Gallia Narbonense and here he obtained the support and the legions of Governor Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, also a Caesarian. Both Anthony and Lepidus were then declared public enemies by the Senate.

The clash between the two armies took place near Modena. Octavius’ army prevailed and, moreover, he happened to be the only surviving commander: the two Consuls had fallen, and Anthony, who had been beaten for the first time in his life, had fled. Thus as the “boy” returned to Rome at the head of all the troops stationed in Italy, he went to the Senate and imposed his appointment as consul, together with the annulment of the amnesty for the conspirators of the Ides of March and their death sentence.

Now, even Octavius was getting unpopular with the senators, who realized that he had no intention to be their instrument. So, Octavius summoned Anthony and Lepidus to Bologna and established what has been called “the second triumvirate” with them. He had learnt his uncle's lesson very well.

The three leaders had the popular assembly pass a law by which triumvirs were appointed for the reform of the state with a duration of 5 years, renewed for another 5: they had the right to make laws, appoint magistrates, judge without appeal against their sentences, decide peace and war, assign the land. The Senate bowed. Caesar had died, but absolute power had not: only, it had passed on to the two lieutenants and the dictator's adopted son.

Guards were stationed at all gates of the city, and the great vengeance began. Three hundred senators and 2000 officials were charged with the murder of Caesar, tried and killed, and their assets seized. A bounty was also put on the heads of those who fled, but most preferred to kill themselves, and in the gesture, they had the style of the great ancient Romans. The tribune Salvius, for example, gave a banquet, drank the poison and his last will was for lunch to continue.

The most greedy prey for Anthony was Cicero, the great former consul and senator, who had opposed him. He tried to escape, but Anthony's patrols swooped on him at the port of Formia. Cicero meekly offered his neck, and his decapitated head was carried to the triumvirs, together with his right hand.

Now the two main culprits, Brutus and Cassius, who, as governors of Macedonia and Syria, had joined forces and formed the last army of republican Rome, remained to be punished. The battle took place at Philippi on September 42. Brutus broke Octavian's line, but Anthony broke into Cassius's side. Cassius was killed by an attendant and, after a chase, Brutus also suicided. Anthony searched for his corpse and, when he found it, he pitifully covered it with his purple tunic: he remembered that Brutus had asked the conspirators to spare him.

At this point, the triumvirs divided the territories of the Republic among themselves: Octavian had Europe, Lepidus Africa, and Anthony chose Egypt, Greece and the Middle East. Each of them knew that the accommodation was temporary, each of them hoped to take the other two out, sooner or later. The most confident was Anthony, who believed in military force and knew that he was, as a general, superior to the others.

Caesar had been eliminated, but Caesar's armies remained, and it was the men who led these armies who competed for absolute power. In the years ahead, the power game would be played only between Caesar's adopted son and Caesar's right-hand man, between Octavius and Anthony: now allies against the Senate, soon again rivals and finally open enemies. One thing was sure: the times of the Roman Republic were over.

On January 10th of the year 49, Caesar "cast the die", he passed the Rubicon with the Legion XIII, 6,000 men only, against the 60,000 that Pompey had already gathered. The Legion XII reached him in Piceno, and the Legion VIII in Corfinio, halfway between Pescara and Rome; the cities opened before him and greeted him like a God. Italy was exhausted and did not resist the rebel, and he repaid it with clemency: no looting, no prisoners, no purges. Caesar kept on seeking a compromise during this advance on Rome without resistance or at least pretended to. But without waiting for answers, he kept on advancing. Pompey and his senators were caught off guard by Caesar's bold and decisive gesture and by the favour he enjoyed; they preferred to leave Italy without fighting, also because the legions of veterans Pompey could dispose of had fought in Gaul in Caesar's service, so their fidelity was uncertain.

Pompey retreated to Brindisi, where he loaded his army on the ships and ferried it to Durazzo. Curious tactics for a general who had at least twice as many men as his opponent. Actually, Pompey counted on the aid from the eastern provinces, taking advantage of the influence he had gained in those lands at the time of the wars against Mithridates, 20 years before. The conservatives, laden with money, pretensions, insolence, each with servants, wives, friends, luxury tents, uniforms and plumes, abandoned Rome in the wake of Pompey after declaring that the senators who remained there would be considered enemies of the Republic.

Caesar entered Rome on March 16th, leaving the army outside the city. He had rebelled against the Republic but respected its regulations. He asked for the title of dictator, but the Senate refused. He also demanded that peace envoys be sent to Pompey, and the Senate refused. He asked to have access to the Treasury, and the tribune Lucius Metellus opposed it. In the end, he declared: “it is as difficult for me to make threats as it is easy to carry them out”. Immediately, the treasure was made available to him.

The Conservatives prepared to counter Caesar by amassing three armies: Pompey’s in Albania, Cato’s in Sicily, and another in Spain. Pompey expected Caesar to head to the East, but after staying in Rome for only eight days, Caesar went to Spain first, to secure wheat supplies and get rid of the enemy forces in the peninsula. He believed that the Pompeians were not so strong, and he faced unforeseen events and difficulties. But he gave his best in times of danger and, in just two and a half months, all the enemy legions surrendered.

The people in Rome, who had been saved from famine, exulted. The Senate gave him the title of “dictator” and, to set things right, Caesar had the People's Assembly proclaim him Consul. Now Caesar was impatient; he wanted to engage Pompey’s army in battle as soon as possible because time was on Pompey’s side, he kept on receiving soldiers from his allies. So, Caesar gathered the army in Brindisi, boarded 20,000 men on the 12 ships he had at his disposal and landed them in Albania, on the other side of the Adriatic Sea, on the trail of Pompey.

Pompey was stunned: he was convinced that no one would dare cross that arm of the sea in winter, which was patrolled by his mighty fleet. Why didn't he attack that reckless enemy, who dared to defy him with so little force, we’ll never know. The weather also favoured Pompey: Caesar's ships shipwrecked, and thus he could not ferry the rest of the army.

The weather finally got good again, and Mark Antony, the best of his lieutenants, with other men and supplies could reach Caesar's demoralized troops. On Pompey’s side, most of his followers persuaded him to look for the fight because they were convinced that Caesar would lose. Pompey ran after the enemy and reached him in the plain of Pharsalus, in Thessaly. He had 40,000 infantrymen and 3,000 cavalrymen; Caesar, 22,000 infantrymen and 1000 cavalrymen. There were great banquets, speeches, drinks, and toasts to celebrate the victory in Pompey's camp on the eve of the battle. Caesar ate grain and cabbage with his soldiers in the mud of the trenches.

The next day, August 9th, 48 BC, Caesar made his masterpiece: Caesar's veterans, whom he had personally trained and led in the battle for so many years, defeated Pompey’s troops, which were less prepared and less motivated, as they were composed mainly of newly enlisted soldiers and auxiliaries provided by provincial communities and client kings. Caesar's army lost only 200 men, killed 15,000, and captured 20,000; Caesar ordered them to be spared and celebrated the victory under Pompey's luxurious tent, eating the lunch that the cooks had prepared for Pompey to celebrate his triumph. After Pharsalus, many Republic supporters preferred to surrender. In fact, Caesar had repeatedly guaranteed that the defeated enemies who surrendered could pass on his side or return unharmed to their private life.

At that moment, Pompey was riding towards the port of Larissa, always followed by a disturbance of aristocrats. There was also a Brutus; he was the son of his old mistress Servilia, and perhaps Pompey was even his father. From Larissa, Brutus sent Caesar a letter asking him for forgiveness for himself and his brother-in-law Cassius, and Caesar immediately acquitted both of them. A gesture that will cost him dearly.

Pompey’s wife had joined him, and he embarked for Africa, intending to put himself at the head of the last senatorial army, the one Cato and Labieno had been organizing in Utica. The ship anchored in front of a port named Pelusium, in the waters of Egypt: Egypt was a vassal state of Rome, which administered it through its young king, Ptolemy XIII. Ptolemy was a young boy at the mercy of his prime minister, Potinus. He already knew about Farsalus and believed he was securing the winner's gratitude by assassinating the loser. As he disembarked from a lifeboat, Pompey was stabbed in the back under his wife's eyes. And, when Caesar arrived, Pompey’s head was presented to him: he turned away with horror.

Now that he was there, before returning to Rome, Caesar wanted to fix things in that land, which had been going wrong for a long time. According to their father’s will, Ptolemy was to share the throne with his sister Cleopatra after marrying her; this was quite common in ancient Egypt, where pharaohs almost always married their sisters. But when Caesar arrived, Cleopatra was not there: Potinus had confined her and locked her up.

Secretly, Caesar sent for her. To reach him, she had herself hidden in a carpet that the servant Apollodorus brought to the apartments of the illustrious guest at the Royal Palace. When the carpet was opened, Caesar found himself in front of a woman, and what a woman!

Cleopatra was not beautiful but sexy, an expert in cosmetics and powders, with a melodious voice. Besides, she was very curious and cultured; she knew the basics of astronomy, geometry, arithmetic and medicine. She was very skilled in rhetoric, and above all, according to Plutarch, she knew at least eight languages, among them Greek and Latin. And Caesar, who was an inveterate womaniser and was also 52, certainly did not back down.

The next day he reconciled brother and sister, that is, he practically gave all power back to her; Potinus was suppressed, discreetly, on the pretext that he was conspiring. But at this point, the whole city rose against Caesar, and the local garrison joined the rebels. With his few men, Caesar turned the Royal Palace into a fort, sent a messenger to his troops in Asia Minor to ask for reinforcements, burnt the fleet so that it did not fall into the hands of the enemy (and unfortunately the fire spread also to the great library, honour and pride of Alexandria). He himself led an assault on the islet of Faro by swimming; here, he waited for reinforcements to arrive. Cleopatra bravely stayed with Caesar; when reinforcements arrived, they easily defeated the Egyptians.

Caesar had prevailed, and promptly he put Cleopatra back on the throne. He stayed with her for nine months, the time it took her to give birth to a child who was called Caesarion so that there was no doubt about who was the father. At least on Caesar’s part, it had to be love to make him deaf to the appeals of Rome; in his absence, the city had fallen prey to the violent squads, led by a Milo. The young queen had earned Caesar's support by exploiting her feminine charm and the weapons of seduction. But at the news that he was about to embark on a long journey with her on the Nile, Caesar’s soldiers rebelled. Caesar then shook himself, put himself again at the head of his troops and first set out for Asia Minor.Here Pharnaces, king of the Bosporus (present-day Crimea) and son of Mithridates VI, was trying to take advantage of the Roman Civil War to expand his kingdom. It was a very short campaign: after a few weeks, Pharnaces was defeated at Zela; when Caesar celebrated the triumph in Rome, he displayed a sign with only three words: "Veni, vidi, vici", I came, I saw, I won.

Then, he embarked for Taranto, taking Cleopatra and their child with him; and as if nothing had happened, he showed up in Rome and to his wife Calpurnia with this living prey of war. Calpurnia did not blink; she was used to her husband's infidelities. The situation in Rome was not good. Grain no longer came from Spain, here Pompey's son had organized an army, and not even from Africa, here Cato was dominant, his forces were equal to those that Pompay had in Pharsalus. In Italy, it was chaos. Caesar had instructed his lieutenant Mark Antony to maintain order, but Antony was a soldier and solved problems the only way he knew, by unleashing his troops. 1,000 Romans had been slaughtered in the Forum, and Milo had fled to organize the revolt outside Rome; here, several legions had rebelled.

To solve the problem, Caesar began from the army. He presented himself, alone and unarmed, to the legions that had revolted. With his usual calm, he said that he recognized their legitimate claims and would satisfy them on his return from Africa. To Africa, he would go with other soldiers. At those words, veterans rose, they shouted that they were Caesar's soldiers, and they intended to stay so. Caesar pretended some difficulties, then surrendered for the simple reason that he had no other soldiers.

He loaded the troops on the ships, landed in Africa in April 46 and found 80,000 men waiting for him under the command of Cato, his former lieutenant Labienus and Juba, the king of Numidia. Once again, he lost the first battle and, once again, he won the decisive battle, which was terrible. Cato, his primary opponent, ran back to Utica with a small detachment, advised his son to submit to Caesar, offered lunch to his closest friends, entertained them about Socrates and Plato. Then he retreated to his room and plunged a dagger into his belly. When he knew, Caesar sadly said that he could not forgive him for taking away the opportunity to forgive him, then he gave Cato solemn funerals and offered his pardon to his son.

After a brief stop in Rome, Caesar embarked once again for Spain to get rid of the last Pompeian army and defeated it in Munda. No one could now oppose Caesar's absolute power; in 47, the Senate had granted him the title of dictator for ten years and then for life.

Caesar was back in Rome in October (after all, he’ll stay in Rome for no more than five months before being assassinated). He took the title of imperator, he could then pass it on to his descendants, and every day he could wear the laurel wreath, the victorious generals wore it only on the day of triumph. His statue was erected among those of the ancient kings of Rome and, in his honour, the fifth month after March, which was the first month of the archaic Roman calendar, was given the name “Iulius”, hence Luglio in Italian and July in English.

After so much war, there was no one left to fight. It looked like peace could last for years, and Caesar devoted himself entirely to the work of reorganizing the State. Formally, the Republic, with its magistrates and assemblies, was still operational. Still, civil, military and religious powers were practically in the hands of a single individual, who acted as a magistrate but in reality had no constraints on his decisions.

The assembly was on his side, and Caesar reduced the Senate to a purely advisory body. Members grew from 600 to 900, with new elements chosen partly from the Roman and provincial bourgeoisie and partly among his old Celt officers, many of whom were children of slaves. He granted Roman citizenship to Gallia Cisalpina, which he had known and ruled as governor; now Italy was Roman, from the Alps to the Strait of Messina, both culturally and legally. And he began to reform the bureaucracy and the army with these provincials of peasant or bourgeois origin.

To reward his veterans and solve the problem of urban, poor citizens, he distributed land to 80,000 heads of families. To avoid expropriating lands, he founded a series of colonies in Gaul, Greece, Carthage.

Also, to have more agricultural land available for distribution and at the same time get more opportunities for work for the urban plebs, Caesar planned the reclamation of the Pontine Marshes, south of Rome. He ordered important public works in Rome: the Forum was renovated, the Basilica Giulia and a new Curia for the meetings of the Senate were built. He also decided to create a new Forum next to the Roman Forum, which was now insufficient for the needs of Rome.

The Forum of Caesar was the first of the Imperial Fora to be built, starting from 54 B.C., as an extension of the ancient Roman Forum. The Forum was built on an area previously occupied by private buildings, which Caesar purchased for an enormous sum, between 60 and 100 million sestertii. Caesar built his Forum following a vow he had made before the Battle of Pharsalus against Pompey, and it was dedicated in 46 B.C.: the work, which remained incomplete, was finished by Octavian after Caesar's death, and a new inauguration took place on May 12th, 113 AD, under Emperor Trajan. The area occupied by the Forum measured initially about 160 m by 75 m, surrounded on three sides by a double colonnade. In the centre of the square stood the statue of Caesar, on a horse whose forelegs had the shape of human feet. The south-western side consisted of a series of shops of varying depths, built with blocks of tuff and travertine. The Temple of Venus Genitrix occupied the bottom of the square and was its real architectural and ideological fulcrum. A statue of Venus Genitrix, the mother of Aenea and the mythical progenitor of the "gens Iulia", stood inside the cell.

Caesar put in these enterprises the same energy that he had put in battle. He wanted to see everything, know everything, decide everything. He did not admit waste and incompetence. The policy of full employment coincided with his ambition to build grandiosely; Caesar was a builder, as he had shown when he was a general. He also innovated the calendar: to heal the growing disagreement between the calendar year and the actual pace of the seasons, Caesar called a Greek astronomer from Alexandria and introduced a year of 365 days, with a leap year of 366 days every four years: it is the Julian calendar that is still used today, with slight modifications.

He was totally indifferent to the dangers that threatened him. He could not ignore that many were plotting around him, but he did not consider his enemies brave enough to dare. And he dreamed of new enterprises: avenging Crassus against the Parts, extending the empire over Germany, finally refounding the whole of Italian society based on the ancient customs.

After the death of Silla, power theoretically returned to the Senate. Still, the Senate itself leaned on two lieutenants of Silla, the most potent individuals now in Rome: Pompey and Crassus.

From a wealthy family, Marcus Licinius Crassus had become even richer with the confiscations during the times of Silla, and this wealth allowed him to play a major political role. In 73, slaves at a gladiator school in Capua revolted; they were gladiators, therefore they were well trained and prepared. They were led by a slave from Thrace, Spartacus, who knew the Roman military tactics because he had fought in the Roman army. The revolt started with a small group of skilled fighters, but it quickly spread to large areas of southern Italy; it was a clear sign of the desperation of thousands of slaves; and surprisingly, they were joined by many peasants and small farmers, for many Roman citizens the living conditions were so poor that they chose to join the slaves in the revolt.

To fight this war, which was called "the slave war", the Senate gave Crassus the command of 8 legions, some of which he probably financed himself. After a great battle in Apulia in which Spartacus died, in 71, the war was over: Crassus had 6.000 prisoners crucified along the Appian Way.

The other protagonist of these years is Pompey: after being a supporter of Silla, in 76, he was sent to Spain to fight the Roman governor Sertorius, who ruled his provinces as an independent king. After taming the revolt, he returned and signed a pact with Crassus: both would be consuls in the following year. And so it happened. But it was Pompey that the Senate appointed as leader of a great army to fight pirates in the western Mediterranean.

With extraordinary powers and an army of 120,000 soldiers and 500 ships, Pompeius got rid of the pirates and cleared the sea routes in a few weeks. Then he was ordered to turn against King Mithridates of Ponto (now Armenia), but he went far beyond his mandate: he defeated King Mithridates, subdued Armenia, annexed Syria, and intervened between the two heir brothers to the throne of Judea, and made it a tributary state.

Now the Eastern Mediterranean was controlled, directly or indirectly, by Rome. Pompeius acted without even caring to be authorised by the Senate; he acted on his own initiative, as a monarch: he deposed kings, created others, set territories as Roman provinces, allowed others to remain independent under Rome’s control, which was also a way for him to obtain the future support of these kings. This meant that the Senate, which traditionally had the responsibility of foreign policy, was losing power, and it set a precedent that other generals would follow.

At this point, it was evident that in Rome’s policy, conquest and exploitation prevailed over anything else. Rome no longer needed to justify its aggressive policy since there was no public opinion of any kind anymore; it was the most powerful state in the Mediterranean and thus had the right to dominate all other peoples and establish a universal empire.

Pompey was now immensely rich; he dissolved the army as he was legally compelled to do and returned to Rome in 62. He thought that his popularity and influence were so great as to guarantee him the undisputed supremacy of the state. But he was wrong: now that he did not have an army to back him, senators thought he was not so dangerous, after all. The decisions he had taken in the East were not validated, and his veterans were not even granted the lands he had promised them. This led him to turn against the Senate and look for the help of an old friend, Crassus, and through him of Marius' nephew, who was now the leader of the populares: Julius Caesar.

Caius Julius Caesar came from a poor aristocratic family that traced its origins to King Ancus Martius and the goddess Venus. He was probably born in 100 B.C. He was Marius' nephew, and his family ties put him among the populares. Caesar was a perfect man of the times, elegant, unscrupulous and full of humour.

At that time, the contrast between the senatorial and the popular factions was very violent, and in 74, Caesar left for Cilicia to escape his enemies. A pirate boat captured him at sea, and the pirates demanded 20 talents for his ransom. Caesar replied insolently that it was too low a price for his value, and he preferred to give them 50. He sent his servants to get them; while in prison, he wrote verses and red them to the pirates but also promised to hang them. Which he did because, as soon as he was freed, he ran to Miletus, rented some boats, chased the pirates and captured them, took his money back and had them all slaughtered.

Caesar belonged to an ancient family and its relationships, together with some good marriages and the massive number of votes he literally bought, and he spent a lot of money for them; they secured him a series of important public offices. Finally, in 69, he was appointed Governor of Spain. Here he subdued the area's peoples and brought back to Rome a loot so big that the Senate granted him the triumph.

Back in Rome, Caesar proposed to Crassus and Pompey to forge a three-party private partnership that historians will call “the first triumvirate". Each of the three would manoeuvre the masses of followers at his disposal and pass laws to benefit the other two. Caesar was the least important and influential of the three men, and therefore he benefited most from this pact.

With the support of his new allies, he was elected consul for the year 59. Immediately, he had Pompey’ decisions in the East ratified and lands distributed to Pompey’ veterans. Then, to consolidate the alliance, he gave Pompey his daughter Giulia as a wife. He then appointed himself proconsul (governor) of the provinces of Gallia, for five years, never happened before: thus, he could undertake a lengthy military campaign without having to give up command. His conquest would make him as popular as Pompey and provide his soldiers with enrichment opportunities.